For Perennial Fruit Gardens, Berries Are the Way to Grow

Hardy, easy to cultivate, resistant to disease, and quick to yield, berry bushes are perfect for just about any garden environment. Whether you have a large lot in which to plant fruit-bearing hedges, or a sunny balcony that would be perfect for hanging baskets, there’s a berry plant that’s ideal for your home. Best of all, if you choose a perennial species, you’ll only have to put in a bit of maintenance work now and then in order to enjoy a beautiful, bountiful harvest year after year.

When it comes to choosing a berry bush or shrub for your garden, most birds and animals are wired to regard blue, purple, and red fruits as “ripe”, so if you’ve had any problems with squirrels, raccoons, or voracious birds, you might wish to consider a variety that bears white, green, or yellow fruits instead. The wild foragers will assume that the fruit is unripe, and won’t decimate your crop!

Keep in mind that most berry bushes and shrubs prefer acidic soils, so it’s important to do a soil pH test to determine whether your soil needs any amendments before establishing the bushes: it’s better to test ahead of time than risk disappointment from a failed crop later.

Raspberry

Tart and delicious, raspberries pop up in wild spaces all over the world. They’re as common in woodlands as they are in roadside ditches, and seem to be able to thrive in even the harshest conditions. Although there are a few different species, depending on the country in which they happen to grow, they’re all very, very tasty, and easy to grow. You can grow raspberries from seed, but they’ll take a couple of years before they start to produce fruit—it’s far easier to buy bushes from a local garden centre if you’d like to start harvesting as soon as possible.

Raspberries like a lot of sun, and well-drained soil that’s a bit on the acidic side, but make sure that you don’t plant them in an area that had nightshade plants (tomatoes, eggplant, potatoes) or flowering bulbs in previous years, as those plants can carry a wilting fungal disease that thrives on fruit- and nut-bearing plants.

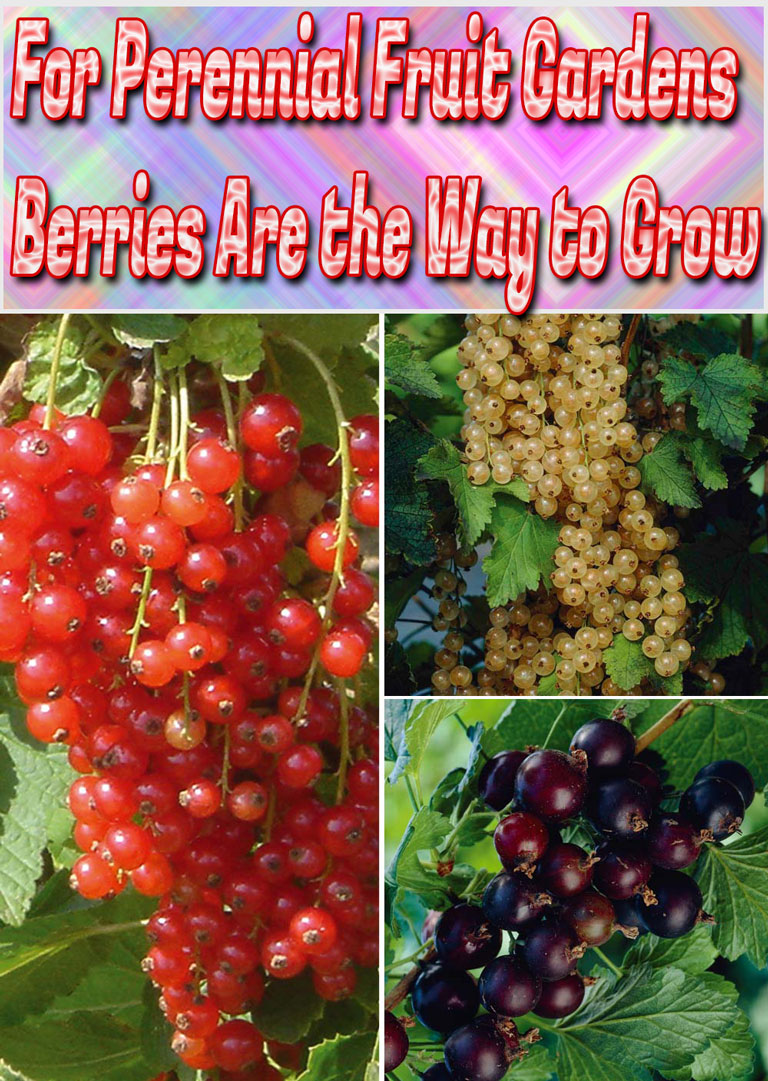

Currant

This fruit is one that nearly any gardener in any zone can plant with hardly any effort whatsoever. It’s cold-hardy, deer-resistant, as beautiful as it is delicious, and comes in several different varieties to suit anyone’s taste and aesthetic preferences. Like most other berries, currants prefer a slightly acidic soil, but will grow just fine in neutral soil as well; just make sure it’s well-drained, cool, and moist, and keep a couple of inches of mulch around the roots at all times. Currants can thrive in partial shade, which is ideal for urban gardens and heavily treed spaces, and will start bearing after 2 to 3 years.

Like golden raspberries, white currants aren’t decimated by birds and other animals the same way that red or black ones are, as the pale flesh registers as unripe to animals on the lookout for lunch.

Blueberry

Who doesn’t love blueberries? These luscious little blue beads have a lovely mix of tartness and sweetness, and are as amazing raw as they are cooked. You can scatter them on your cereal, add them to smoothies, bake them into pies and muffins, or even add them to savory dishes like salads or quinoa bowls.

When it comes to planting them in your own garden, it’s important to plant a couple of different species so they can cross-pollinate: this will encourage your berries to develop larger fruit (and more abundant yields), and if you plant varieties that mature at different times of the season, you can enjoy these luscious berries for a good 2 months every summer. Choose a bright, sunny spot for your plants, and ensure that the soil has plenty of peat moss worked into it. Blueberries enjoy soil that’s quite acidic—pH 4.0 to 5.5 is ideal. If your soil is a bit too alkaline, you can amend it with sulfur the season before you plan to plant your berries, and all should be well.

Serviceberry

There are a couple of different species that are referred to as serviceberries, but the two most common ones are the Saskatoon berry (Amelanchier alnifolia), and the Juneberry (Amelanchier canadensis). Both are flowering shrubs that are native to North America, with the former ranging from Alaska through half of Canada, and into the northwestern USA, and the latter trickling down along the eastern coast from Newfoundland down to Alabama.

I’ve only had Saskatoon berries, but was blown away by their flavour, which is sweeter and “nuttier” than blueberries. They like to grow in soil that’s fairly pH neutral, but be sure that you don’t plant them anywhere near juniper bushes, as they can cause a rust disease on one another. One-year-old bushes are best planted in springtime, and tend to do best on sunny, east-facing slopes.

Gooseberry

There’s really no solid answer as to why gooseberries are named such, since they’re not favoured by any sort of waterfowl, but these sweet, musky berries are fabulous regardless of where their name originated. This is one of the most common and well-loved berries in the UK, and it’s also well-known and adored throughout most of mainland Europe. The berries are wonderful both raw and cooked, and you can find hundreds of recipes for gooseberry pies, preserves, and other desserts. Depending on the variety you choose to plant, you may end up with berries that taste somewhat like apricots, or grapes, or even apple, so be sure to research different species so you know what flavour profile you’ll end up with.

Gooseberries like well-drained, compost-rich soil and plenty of sunlight, and if you plant a 2-year-old bush, you’ll start getting berries the following year. The best yields tend to start when gooseberry bushes are 4 to 5 years old, at which point it’s probably good to have some large empty buckets handy to gather them all.

Honeyberry

Also known as haskap, the honeyberry is an unusually shaped fruit that really should be more popular than it is. A member of the honeysuckle family, its berries taste like an interesting hybrid of blackberries, cherries, grapes, and kiwis, and are great both raw and cooked/baked.

One reason why the honeyberry should be far more popular is that it’s an incredibly hardy plant that can grow in almost any soil, in zones ranging from 2 to 9; it doesn’t need overly acidic soil (a range of pH 5 to 8 is just fine), and as long as it gets full sun and has another variety to cross-pollinate with, you’re good to go.

Blackberry

These succulent, dark, meaty berries leave our mouths and hands purple when we cram them into our faces, and are as great raw as they are in baked goods. (If you’ve never eaten blackberry pie, you must amend that posthaste.) Blackberries grow in wooded areas all over Europe, North and South America, Asia, and even parts of Africa, and are so easy to grow that they can easily become invasive.

Blackberries like well-drained, sandy, loamy soils, and full sunlight, and if you can plant them on a hill or a slope, even better: try to avoid placing them in any low-lying area, as rain and meltwater can accumulate there and drown their roots. As with raspberries, don’t plant blackberries in the same soil where you’ve had nightshades in previous years.

Jostaberry

You won’t find jostaberries mentioned in many old cookbooks because it’s a recent hybrid: a three-way cross between black currants and two species of gooseberry. It was created in Germany in the late 1970s, and has grown in popularity in recent years because of its hardiness and the sweetness of its berries, which are described as tasting like a cross between a blueberry and a concord grape.

Pronounced as “yust-a-berry”, this amazing fruit is hardy to zone 3 and is remarkably disease resistant. It also prefers a compost-rich, well-drained soil and plenty of sunlight, and will start producing fruit in its second year. By year 4 or 5, you can look at a yield of several pounds of fruit per plant, though you probably want to cover everything with bird-proof mesh so they don’t eat everything before you can.

Mulberry

There’s a reason why generations of kids danced around mulberry bushes, singing their hearts out: the berries are absolutely delicious, and singing would probably keep birds away long enough for wee ones to get their hands on the sweet, crunchy little nuggets. This is one berry bush that can thrive in just about any soil as long as it’s moist, and is hardy from zone 4 and upward. Mulberries can also be grown indoors very successfully: you just need a big, bright, sunny window area that’s protected from drafts in wintertime.

It’s best to plant a young shrub from a garden centre rather than trying to grow it from a seed, and if you’re only getting one plant, be sure to get one that is self-fruitful. As a note, the fallen fruits will stain whatever they land on, so it’s best to plant your bushes well away from sidewalks or driveways. If you’re growing them indoors, it’s probably a good idea to keep them on mats that you can dispose of once they’re too heavily stained. Mulberries can grow quite tall, so be sure to cut them back regularly if you’d like to keep them bush-sized.

Strawberry

One of the most well-known and well-loved berries of them all, strawberries are utter delights that pop up every spring/early summer. They’re gorgeous right off the vine, or mixed with coconut cream and a sprinkle of sugar, added to smoothies, made into popsicles, baked into every sort of dessert imaginable, and sliced into salads. Whichever way you like them, strawberries make just about everyone smile.

Most strawberries like compost-rich (and slightly acidic) soil, and full sun, with the exception of the alpine or woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca), which prefers partial shade. I like to grow strawberries in hanging baskets, since I’ll actually be able to enjoy the fruits instead of losing them all to chipmunks, squirrels, mice, and slugs; all of which seem to enjoy them a great deal. When growing strawberries in hanging baskets, make sure there’s a lot of peat moss and compost to keep the roots moist and nourished, and don’t place more than 3 plants in the same hanger, so there’s plenty of room for the roots to spread.

Lingonberry

If you’ve never heard of a lingonberry before, don’t feel bad: they’re most popular in northern Europe (the Scandinavian countries in particular), and just a few areas of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, where they’re known as “redberries” or “foxberries” respectively. Nearly as tart as cranberries, lingonberries are loaded with vitamin C, and have been a staple food for both people and wildlife for thousands of years.They’re normally blended with sugar or honey before being eaten, and if you ever visit Sweden, you’ll likely come across lingonberry jam, jelly, juice, and even sauce or gravy. In Denmark, the berries are often used alongside currants and other red berries to create the signature rød grød med fløde sweet berry porridge normally served with cream.

This is a short, low-growing evergreen shrub similar to a low-bush blueberry, but it will not do well in a warm, dry climate: lingonberries need cold winters and moist soil in order to thrive. In areas that get really brutal snowfalls, you’ll want to cover the bushes with burlap, but they’re hardy enough to withstand temperatures down to -30F. Although you might have a “yay” moment if you live in a colder zone and realize that you can grow these easily, take note that they’re really slow to establish, and it could take up to 5 years before you see a single berry.

Elderberry

Gorgeous in jams, jellies, pies, cordials, and wines, elderberries have been treasured little fruits since the dawn of time. You have to be sure to cook the ripened berries well, however, as they’re quite toxic if eaten raw. (No, you won’t die if you eat a handful of raw berries, but you will get rather ill… in all directions.) The berries are high in vitamins C and B6, and a simple Google or Pinterest search will yield countless recipes for them, including delicious home remedies for colds and flus.

Plant 1- or 1-year-old bushes in well-drained, damp soil, in a patch that’s either sunny, or just partially shaded. You’ll have to plant another variety of elderberry within 60 feet so the two can cross-pollinate, and be sure to treat them to a great compost mulch every year. By year 4, you can expect about 15 pounds of fruit from each tree, especially if you keep birds away with netting.

If you’re planning to add a few berry bushes and shrubs to your garden, it’s good to have a few different varieties that ripen at different times of the year: that way, you can ensure that you have a steady supply of fruit from spring right through autumn. A good blending would be something like this:

- Strawberries for early June (or all-season strawberries to keep coming up until autumn)

- Saskatoon berries for late June/early July

- Raspberries and gooseberries for July through to early August

- Elderberries for August through September

Be sure to do your research before planting anything to ensure that you get the fruit plants that are best for your growing environment, and keep in mind that some plants (like elderberries) need to have other similar plant species nearby in order to cross-pollinate. When in doubt, schedule some time with a consultant at your local garden centre or organic nursery. Most importantly, enjoy the process! Growing your own food is fun and rewarding, and if you get the entire family involved, chances are that everyone will gain a greater appreciation of where food comes from, and how amazing it is to grow your own.

Leave a Reply