When I was a kid I remember a friend coming late to school after her allergy testing appointment. The inside of both her arms sported dozens of tiny prick marks lined up in rows in various states of swelling and redness. Each spot was a reaction from a different allergen. She had dozens of them lighting up her arms like switchboards.

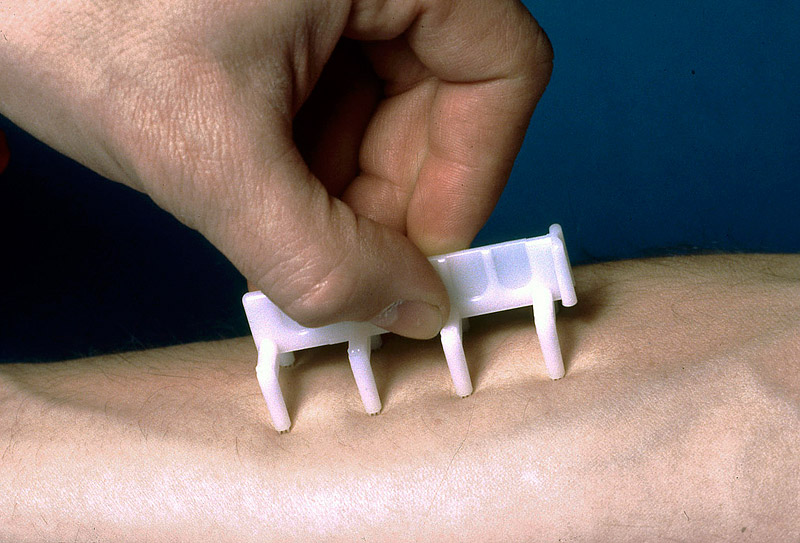

It looked brutal, but she wasn’t complaining. Good thing, since not much has changed since then and skin prick testing is still the gold standard. What has changed slightly is the method of injecting the allergens into the skin. “The one I like to use doesn’t use needles; it uses a special plastic applicator with brushes on it,” says Howard Druce, a board-certified allergist in private practice in Somerville, N.J., and clinical professor of medicine at Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School.

“We take extracts of all the things people are commonly allergic to — pollens, danders, molds, all the things in the environment that people breathe in or get in their eyes and causes symptoms and we put this into the skin very superficially — it’s not painful,” says Druce.

Some allergists still use tiny traditional needles. The tests are always applied in the same pattern so there should be little cause for misdiagnosis of which allergen set you off. If you’re allergic, the prick mark swells and reddens in 10 minutes — leaving a mark both the doctor and the patient can see.

Patients who take an antihistamine have to stop a few days to a week before the test for accurate results. Other drawbacks with skin testing include unpleasantness for some and hard-to-read results for those with dark pigmented skin.

In addition to the skin prick test, there are several other methods to check for allergies.

Patch test

The patch test checks for allergens that have come in contact with the body and caused a reaction. If someone gets an itchy rash after wearing jewelry or they get a reaction after applying makeup, these things can be tested by wearing a patch of that allergen for 24 to 72 hours. Metals like cobalt and nickel, additives in cosmetics, like balsam of Peru, and hundreds of additives and ingredients in laundry detergents and products can be tested.

It’s not particularly fun to wear a patch that causes an itchy rash for three days, explains Druce. “If you know cheap jewelry causes an itchy rash, there is an easy solution to that rather than testing.” He doesn’t typically recommend patch testing; instead he suggests using laundry detergent without phosphates and fragrance and trying to avoid suspected culprits.

Challenge or provocation testing

Challenge testing, also called provocation testing, is the best option for food allergies, but it’s time-consuming, expensive and not often used, says Robert Reinhardt, medical director at Thermo Fisher Scientific and a professor of family medicine at Michigan State University. Patients are put in a controlled medical setting like a hospital (in case of severe reaction) and are given small amounts of food to see which foods produce an allergy. It’s often blind or double-blind in that the patient, the clinician or both do not know each food given. Tests are designed to provoke a response. This kind of testing is also performed for inhaled allergens, in which the patient is similarly exposed to real inhaled substances via the nose, eyes and lungs to test for a reaction.

Blood testing

Blood allergy testing can measure more than 650 allergens, including all pollens, weeds, grasses, trees and mold; 200 common foods; and some drugs and occupational exposures. “Most modern blood testing compares favorably with skin testing,” says Reinhardt.

A positive result to a blood allergy test means you were exposed to an allergen and your body produced IgE, a type of protein called an antibody, which the immune system produces in response to perceived threats. It doesn’t necessarily mean you’re allergic to all the things you test positive for. For example, someone could eat a certain kind of food every day and still test positive for an allergy to it. “The clinician has to go back to their history and symptoms and put it all together,” Reinhardt says. “History always trumps test results.”

Druce agrees the challenge is interpreting the results against the patient’s symptoms. “Just seeing a positive result doesn’t mean anything — and we see so many positive results in foods.” For example, someone with eczema, which can be related to allergies, may test positive for a food, but the doctor must then find out if eating that particular food makes the eczema worse. If not, it’s not a true food allergy.

The allergy blood test is sent off to a lab and results take one to three days. “I’m biased since I like to do the skin testing and in 10 minutes the patient is still there, and they can see on their arm what they are positive to,” says Druce. “The blood test is not the same call to action as the skin testing.”

What’s the point of allergy tests?

Once you do find what you’re allergic to, an allergist can create a plan of attack that includes avoidance or reducing your exposure with lifestyle changes and simple at-home steps, medications (either over-the-counter or prescription), immunotherapy and allergy shots.

“There are no cures for allergies regardless what anyone says,” Druce says. But embarking on immunotherapy for three to five years can offer a reduction in symptoms and a possible remission of allergies for several years afterward.

Druce cautions that at-home allergy testing kits are not FDA-approved or reliable at this time and not recommended. Patients should see their primary care doctor or an allergist to get tested for allergies and help devise a strategy to reduce their symptoms.

It’s interesting to read about some of the different methods of allergy testing. It makes sense that blood testing could be a good way to find a lot of allergies all at once. It’s something to remember when having my kids tested just to make sure we know what they are allergic to.