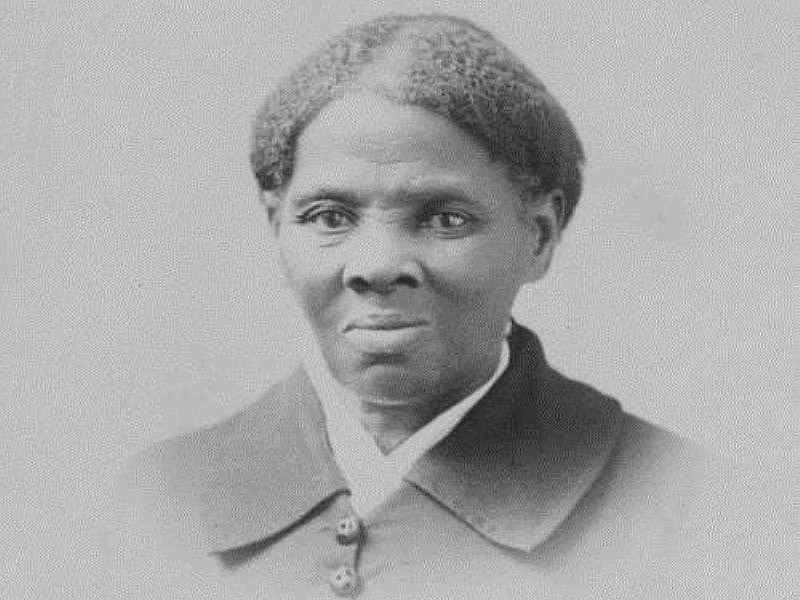

Harriet Tubman, one of the most influential people behind the anti-slavery movement during the 1850s, is set to be honored by the U.S. Department of Treasury by placing her image on the new look $20 bill.

According to the agency, Tubman’s likeness will replace that of former president Andrew Jackson, which will be incorporated in the depiction of the White House at the back of the bill.

Aside from featuring Tubman, the Treasury Department said the redesigned bills will also include other important scenes from American history, such as depictions of leaders from the civil rights and women’s suffrage movements on the $5 and $10 bills. Ellen Feingold, a curator at the National Museum of American History (NMAH), pointed out that the last woman to have her image depicted on a major American banknote was Martha Washington, the wife of former president George Washington. Her likeness was featured on the old $1 silver certificate during the late 1800s.

In 2015, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew revealed that the department was planning on replacing Alexander Hamilton’s image on the $10 bill with that of a woman and asked the public to send in their suggestions.

Some of the names submitted to the agency included Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of former president Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Rosa Parks, who is hailed as “the first lady of civil rights.”

Following the Treasury Department’s announcement, a movement known as “Women on 20s” petitioned the government to have Andrew Jackson’s image removed from the $20 bill. A prominent slave-holder during his time, Jackson is believed to be the one who ordered the forced removal and subsequent genocide of Native Americans.

Underground Railroad Conductor

Harriet Tubman achieved prominence in American history for her efforts in helping black slaves escape the South and reach the safety of slavery-free Northern states.

Having been born a slave herself, Tubman spent the first few years of her life working as a house servant and field hand during the early 1800s. Even back then, she was already well-known among her peers as someone who would always stand up for others.

When one of her fellow field hands got into trouble with their overseer, Tubman tried to step in between them. While she was able to protect her peer, she was hit on the head with a 2-pound weight that the overseer threw at her. She later met a former slaved named John Tubman and the two of them were married in 1844. However, five years later, Tubman was forced to flee for her life after she, her family and the rest of the slaves in the plantation were threatened to be sold off to another master.

Despite not knowing where to go, Tubman kept on running until she met a white woman who helped her. She used the North Star as a guide at night in order to find her way until she was finally able to reach Pennsylvania. She soon found work in Philadelphia and was able to save up some money.

Harriet Tubman was determined to go back to Maryland and help her family achieve freedom themselves. One by one, she was able to save her siblings and even escorted a few other slaves as well. She tried to reunite with her husband, but she found out that he had already taken a new wife.

Seeing a way how she could help other slaves, Tubman kept going back to the South to escort those who wanted to be free of their masters. Harriet Tubman was able to developed clever techniques that allowed her to ensure the safety of the fugitives, including the use of a network of safe houses known as the Underground Railroad, which were managed by fellow antislavery activists.

When the U.S. Civil War erupted, Tubman helped out in the Union Army in different capacities such as a cook, nurse, scout and even as a spy.

She was also a prominent member of the women’s suffrage movement, but her failing health forced her to retire to a home for elderly African-Americans, which she had helped establish. Harriet Tubman died in 1913.

Leave a Reply