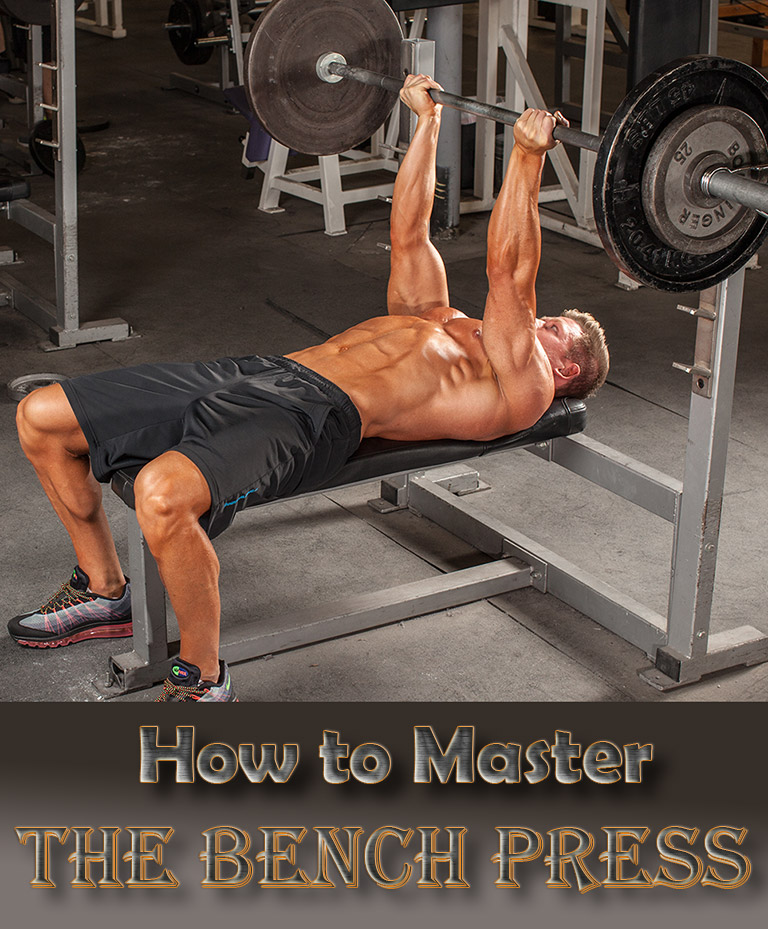

For many lifters, the bench press is the “gold standard” for developing upper body strength, but its reputation invites a lot of ego-driven cluelessness around how to do it with good and safe technique. Its deceptive simplicity is where many new (and even veteran) lifters run into trouble, so let’s talk about how you can bench better and more safely.

For clarity’s sake, we’re talking about the barbell bench press. When you watch someone bench, it looks like the exercise is all arms, chest, and the occasional loud, obnoxious grunts, but it’s actually a compound movement that also includes shoulders, traps, triceps, upper back, core, hips, and even legs to a certain degree.

Why the Bench Press Is Awesome (But Also Dangerous)

Without a doubt, the bench press is a great exercise for improving your “pressing” power for throwing and pushing a heavy shopping cart or lawn mower around, for example. It strengthens your shoulders, develops some sexy pecs (that goes for you, too, ladies) and improves your core strength. In fact, the bench press is a fair indicator of your raw upper body strength and power, and for better or worse, that tends to cloud judgment in the gym.

I’ve seen overconfident lifters get stapled to the bench because they couldn’t get the bar back up off their chest or onto the uprights. Just the other day, a friend of mine recounted a horrifying story of a guy who refused to ask for help, overestimated his ability, and narrowly missed an emergency trip to the hospital. Further still, I’ve heard numerous stories of people who repeatedly press with poor technique in general and a lot of weight, and eventually blow out a shoulder.

In short, the bench press punishes arrogance, but its current reputation unfortunately encourages it. If you’re not careful, the bench press can crush both your ego and your body.

Get a Spotter or Learn How to Bail Out

Safety first. You should have a spotter. Ideally your spot is a lifting partner who knows you and your limits. You can ask some other person in the gym, but the problem with enlisting a stranger’s help is that you can’t be confident in their ability to properly spot.

Still, if your only option is some dude, then very, very clear communication is key: say what you’re going to do (a new one-rep max, for example), agree on the signals for when you really need an assist, and sync up on the countdown to when you and your spotter un-rack the bar and get it handed to you (the hand-off, as it is called).

If there’s no one else around, the other option is to learn how to “bail out” of a bad lift. One particular method is benching without clipping in the weights. So if you get stuck, you can tip the bar to one side, dump the weight, and free yourself. It’s not graceful, but it gets the job done.

Additionally, Omar Isuf, a strength performance coach from Toronto, suggests benching in the power rack. Of course, you have to make sure the power rack is empty, pull a bench up to it, and endure some judgmental stares. But it’s all good because if you get “pinned”, you can rest the barbell on the safety pins in the power rack instead of, you know, on your sternum.

I always say to prioritize safety and practice form with every weightlifting exercise, but I’m slapping on an extra parental advisory sticker on the bench press: it is way more technical than it lets on and opens up far more ways to literally hurt the uninitiated than other exercises do. Essentially, don’t be dumb.

A Good Press Starts Before You Even Lift the Weight

Setting up for the bench press is more than just lying down on the bench. You want to be in the best position for yourself to give that barbell a badass heave-ho, but also avoid spending too much energy un-racking and losing focus.

To get you started, this video by Isuf helps you find your bench press setup groove by going over a few very important “to do and not do” points. Here are more things in mind:

- Healthy shoulder motion: While the bench press is an excellent upper body exercise, it’s also an easy way to agitate your shoulders. This is especially true if you have a history of shoulder injuries. Dean Somerset, an exercise physiologist based in Edmonton, told me that if you have a full range of motion in your shoulders (you can scratch your shoulder blades or get both arms overhead with your biceps touching your ears) and can press in general without pain, then you’re golden. Otherwise, you should really work on getting better range of motion.

- Bar height: Where you set the bar at rest on the rack depends on your arm length. Typically, you want to make sure the bar can easily clear the uprights when your arms are fully extended. If you have to move your shoulders forward to reach up, then it’s too high. If your elbows are bent in the starting position with the bar un-racked, it’s too low.

- Head position: Your head position helps you set up your back on the bench. Most people position their forehead under the bar. In general, you want to be far enough that you can move the bar up and down without the bar catching any parts of the equipment, but also be close enough for un-racking or getting the bar handed to you, if you have a partner.

- Feet placement: Plant your feet firmly on the ground, period. A little known thing about bench pressing is that a lot of power comes from “driving your legs” into the ground as you’re pressing the weight up. You might’ve seen people bench with their feet in the air, but they lose out on a lot of stability and power that way. Somerset says that feet-up-in-the-air may mainly benefit people who have a history of low-back pain and just feel more comfortable pressing this way.

- Grip: Grasp that bar with authority, keeping your grip secure (with your thumbs wrapped around the bar) and your wrist neutral. That means you need to hold the bar in a way that doesn’t bend your wrist back.

- Grip width: Where your hands grasp the bar will depend on your arm length and shoulder width, but the main reason to pay attention to grip placement is so your forearms pretty much stay upright (some say 90-degrees to the floor) throughout. In general, longer arms may need to go with a wider grip, whereas shorter arms may need to be narrower. Most will do just fine around the bar’s knurlings. The nuances here are that a wider grip will focus on the pec muscles a bit more, and a narrower grip will hit the triceps harder.

- Wrist wraps: Special wrist wraps can help stabilize your wrist to keep it in a neutral position and limit movement, according to Somerset. Make sure that the wrap covers the wrist and is tight enough that you can’t pull your hand back once it’s wrapped up, he says. Additionally: “If it’s too low, it’s just a sweatband.”

Remember, you’re holding a lot of weight above your face, so it’s that much more important to know what you’re doing from the get-go. Simply, a good set up makes the rest of it go a bit smoother.

The Infamous “Back Arch” and Why It Won’t Matter to You

The back arch is one of those controversial topics in lifting. Many lifters, mainly those interested in bench pressing a lot of weight, emphasize that the arch (along with the right amount of full-body tension) is crucial for protecting and stabilizing your back and making the move more efficient.

Ultimately, it comes down to whether you’re planning on competing as a powerlifter. In competitive lifting, a highly arched back shortens the distance the bar has to travel from chest to completion (the lock-out) and lets you press more weight. For the rest of us, Somerset notes:

Some people just don’t have the spinal flexibility to make it happen without a lot of low back pain, so it’s very individual in terms of whether someone can or can’t. If you’re comfortable doing it and want to compete, you’ll definitely lift more weight. If not, there’s not much reason to doing it. Go with what you can control and what feels good.

So if someone in the gym is encouraging you to arch your back a ton and youcan’t or don’t want to, just tell him or her to chill out.

The Keys to a Strong, Stable Bench Press

It’s important to watch a good bench press in action. How well you stabilize or brace your body forms the bedrock of a strong, successful bench press. With proper stability, you generate that oomph from your whole body to lift that weight. There are a couple of things that help with that: a deep belly breath, feet placed firmly on the ground, and for some people, that slight (or even an exaggerated) arch in their back we mentioned above.

Beyond that, you’ll still want to keep your upper back (your main support) and butt in contact with the bench, as well as these other key points:

- Move the bar along the right “path”: If you watch a bench press from the side, the bar does not simply travel straight up and down. On the descent, it’s down and slightly arced out. When pressing, it’s up from the mid-chest towards your face and then straight up towards the end of the lift.

- Tuck your elbows: “Protecting your armpits” is the cue that reminds people to tuck their elbows. Your elbows shouldn’t be so close to you that they touch your torso, and your elbows should be directly under the bar the entire time.

- Keep shoulders “packed” throughout: You never ever want to shrug your shoulders forward or have them slide around when you lower and press the weight. Pretend you’re trying to squeeze a grape between them, keeping your shoulders on the bench at all times. The popular cues are to imagine “pulling the bar apart” or “keeping your shoulders down and back”, both of which help you add adequate tension to your body and protect your shoulders.

- Dig your body into the bench: In the bench press, you’re going to be using a lot of “leg drive”, which is why I prefer feet placement on the ground over letting them dangle in the air. When you actually press, imagine pushing your body into the bench rather than merely thinking about pushing the bar away from you.

- Your entire body needs to be tight: Imagine, if you will, that you need to try balancing a full cup of molten lava on your chest. The tightness from bracing your abs, shoulders, and butt keeps you stable so it won’t spill over. To control this stability, it helps to use a breathing technique that we outlined in our article on better breathing for weight training. Speaking of breathing, Somerset suggests taking a breath in, lowering the weight, pressing it up with the shoulders still tensed, and breathing out once the weight gets about half way up.

Those are some of the major things, but there are so, so many moving parts during a bench press that it’s difficult to address the issues that could pop up in your specific case. Obviously, it’s best to have a professional teach you or critique your form.

With a little homework and a lot of practice, you’ll get the benefits of a good-looking bench, and do it safely every time.

Leave a Reply