Despite all the dangers of consuming too much sugar, we still love the sweet stuff. There are a lot of low-calorie sugar alternatives to choose from, but sweeteners made from monk fruit are a healthy standout.

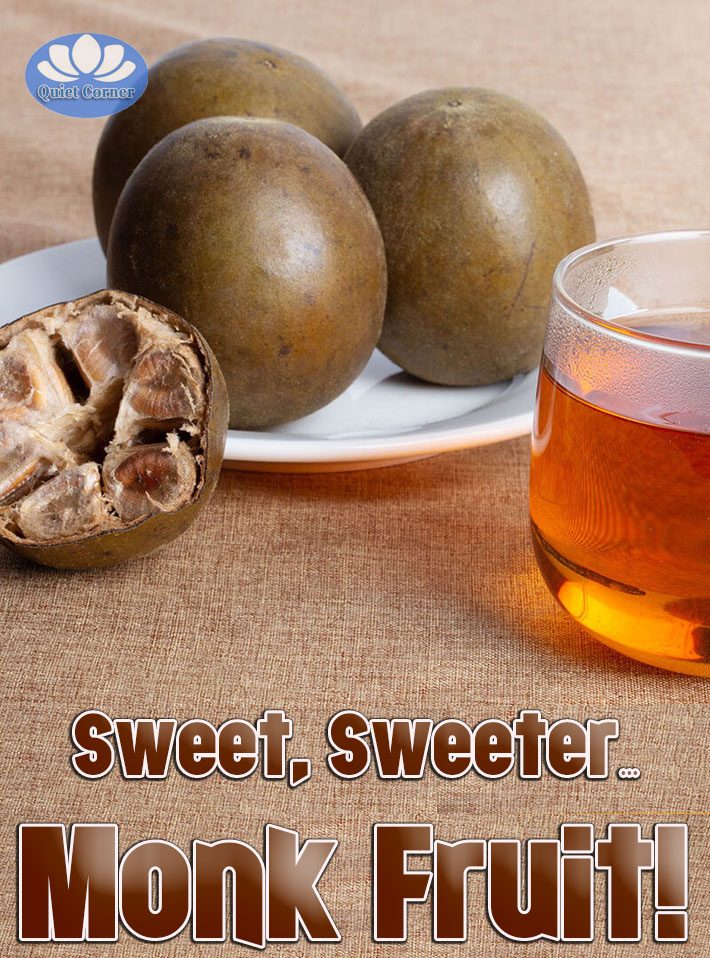

Monk fruit/ Luo Han Guo is from the Curcubitaceae family of plants (other members of this family include cucumber, watermelon, and pumpkin). Native to southern China and northern Thailand, monk fruit is a green, apple-size gourd with super sweet juice (about 300 times sweeter than cane sugar)—yet it has no calories.

Unlike sugar, monk fruit doesn’t contribute to obesity or diabetes. The fruit has been eaten in the Far East for several hundred years, but it does have a few drawbacks to consider.

Taste

Instead of fructose, which is the sugar that typically gives fruit its sweet flavor, monk fruit’s sweetness comes from unique antioxidants called mogrosides. In addition to extraordinary sweetness, mogrosides have other flavors that modern food manufacturers do their best to eliminate.

In 1995, Procter and Gamble patented a process to remove most of monk fruit’s peculiar taste, while retaining its coveted sweetness. The end result is a product more palatable than stevia—another natural, no-calorie sweetener with a licorice-like bitterness. However, even with processing, monk fruit products may still taste a bit odd to some.

Cost

In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration deemed monk fruit sweetener safe for consumption, but its high cost remains the biggest hurdle to consumers and food manufacturers. It is the most expensive sweetener on the market. It costs about twice as much as stevia products and is many times more expensive than synthetic sweeteners.

The Lankanto brand has a granulated monk fruit based-product that is designed to be used like sugar and sells for about a dollar an ounce. Compare that to Domino cane sugar, which sells for about 6 cents an ounce.

There are several reasons why this fruit is so costly. It takes a lot of monk fruit melons to make a little sweetener, and the industrial refining process also adds to its expense. On top of this, a 2004 Chinese law forbids monk fruit seeds or the genetic material necessary to propagate a plant from leaving the country.

But even if you were to procure some seeds, the plant is still difficult to grow outside its native habitat. According to a report from Food Navigator-Asia, 90 percent of China’s monk fruit production comes from Guangxi Province, resulting in a supply that can’t keep pace with the world’s growing demand.

To offset the cost and tame its intense character, manufacturers nearly always mix monk fruit extract with other sweeteners, such as dextrose, stevia, inulin, or sugar alcohols such as xylitol or erythritrol. The result is a less expensive, more versatile product with a few more calories, depending on which sweeteners are added to a particular blend.

Monk Fruit in Chinese Medicine

This fruit and its extract is popular in Traditional Chinese Medicine, and is slowly gaining recognition in other places because of its potential benefits. Monk fruit’s reputation as a sugar substitute is a rather recent development. It has a much longer history as a traditional Chinese herb.

Monk fruit use began in the 1200s when monks in southern China introduced a strange fruit that became known as “luo han guo” or “Arhat fruit.” An Arhat is an entry-level Buddha. This fruit is traditionally grown on mountainsides in Guangxi and Guangdong provinces. These special, subtropical growing conditions meant it was slow to spread to other regions, but its healing virtues gained the attention and respect of local herbalists.

In herbal medicine traditions, plants from the Curcubitaceae family are used to cool the body, and monk fruit excels in this regard. It is traditionally used to brew a cooling tea to combat the oppressive heat of summer or bring down a fever or other signs of internal heat. This makes monk fruit an exceptional sweetener: While sugar feeds inflammation, monk fruit cools it.

Monk fruit has other healing qualities, too. In Chinese medicine, it is used to treat a sore throat, chronic bronchitis, diabetes, and constipation.

Unless you visit southern China, you’re not likely to encounter a fresh specimen, but some Asian markets may carry dried monk fruit. It is much less expensive than the processed sweetener but it comes with a strong, odd taste.

Sometimes it’s mislabeled as “bitter melon,” which is a completely different plant with a gourd that looks like a bumpy cucumber. Dried monk fruit is round, brown, and a bit fuzzy. No bumps.

Monk fruit is increasingly found in a variety of junk food products (such as sodas, baked goods, and hard candy), with a nutritional profile that will appeal to health-conscious consumers. For use in home cooking, monk fruit-based sweeteners are available as a powder or a liquid extract.

Leave a Reply