The neuroscience world is abuzz with news of a successful clinical trial involving a Aducanumab, drug that appears to dissolve protein plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s sufferers, resulting in cognitive improvements. However, it is worth noting that these results, which appear in the journal Nature, relate only to a phase 1b trial, which focused mainly on verifying the safety of the drug on a relatively small number of people, meaning larger phase III trials will be needed in order to confirm the true extent of the medicine’s efficacy.

These trials are currently underway and are expected to continue until 2020 at the earliest, although even at this early stage, the research looks promising.

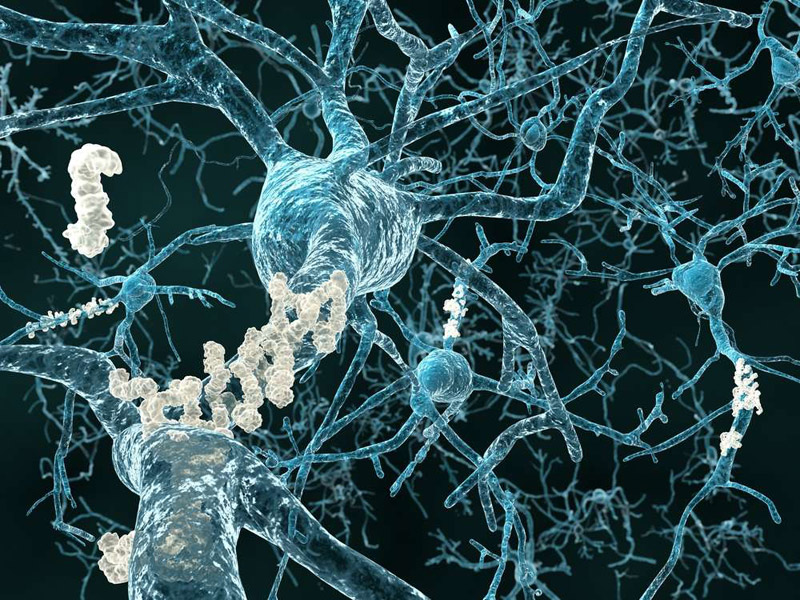

Alzheimer’s disease is an age-related neurodegenerative condition that is thought to be at least partially caused by the build-up of amyloid-beta proteins in the brain, resulting in the formation of plaques that somehow damage synapses, the connections between neurons. Most experimental treatments for Alzheimer’s therefore focus on trying to remove these plaques or prevent their formation in the first place.

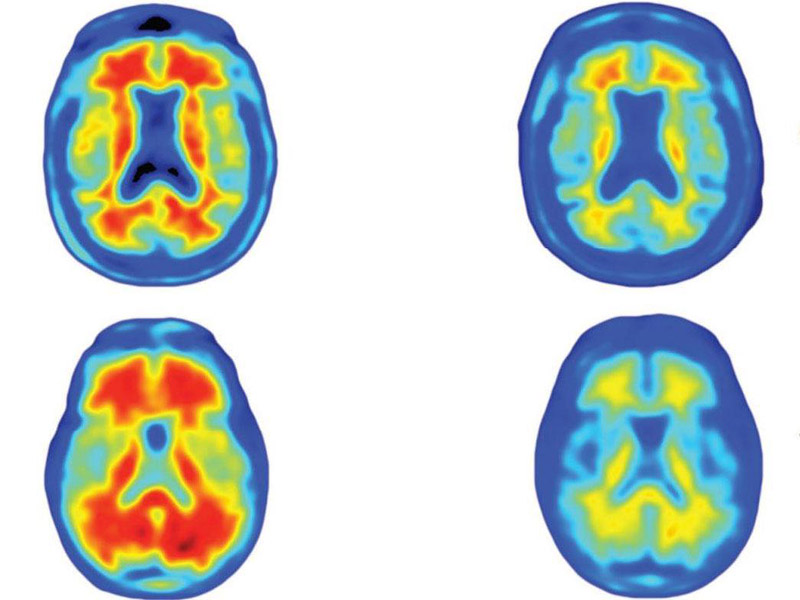

The brains of Alzheimer’s patients, showing how different doses of the Aducanumab reduced the number of amyloid plaques, in red, over a year

In their study, the researchers reveal how they used a human antibody called Aducanumab to remove amyloid-beta plaques from the brains of mice that had been bred to be particularly susceptible to Alzheimer’s. Following the success of this pretrial experiment, they then progressed to a human study, administering Aducanumab to a group of 165 people.

Participants received either the drug or a placebo once a month for a period of 54 weeks, while the study authors monitored the state of the amyloid-beta plaques in their brains using molecular positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Compared to those who were given the placebo, patients who received Aducanumab showed a noticeable decrease in brain plaques after six months, resulting in improvements in their cognitive performance six months later.

Though the researchers are not entirely sure how Aducanumab removes these plaques, they noticed an increase in the concentration of microglia in the brains of patients who received the drug. Since microglia are the brain’s resident immune cells that destroy invading pathogens, the study authors suggest that Aducanumab may recruit these cells to engulf amyloid-beta proteins via a process called phagocytosis.

The build-up of amyloid-beta plaques around synapses is a major indication of Alzheimer’s disease.

The only downside to the study is that 40 participants had to withdraw due to side effects. Around one-third of patients also showed brain abnormalities after receiving Aducanumab , although these tended to clear up after a few weeks, and no one involved required hospital treatment.

While there is still some way to go before the efficacy of Aducanumab as an Alzheimer’s treatment can be confirmed, study co-author Stephen Salloway described the results of this study as “the best news we’ve had in my 25 years of doing Alzheimer’s research.”

Leave a Reply