Members of a Southland family who were struck by lightning are speaking out for the first time since the incident in hopes their story will provide valuable scientific help. Michael McQuilken was 19 years old when he was on a trip to Sequoia National Park in 1975 with his 16-year-old brother, Sean, sister, Mary Sutton, brother, Jeff, and friend, Margie Warthen.

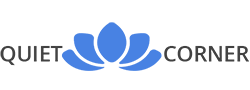

The photo has been reprinted, posted and passed around for decades: Two grinning brothers, hair standing on end, unaware that they were minutes away from being struck by lightning while climbing Moro Rock in California’s Sequoia National Park.

“We were from San Diego and really stupid,” says Michael McQuilken, who was a long-haired 18-year-old when the snapshot was taken on Aug. 20, 1975. His brother Sean was 12.

“We wanted to go up Moro Rock,” McQuilken said. “It didn’t appear to be as overcast; there were blue patches of sky, some sunny areas. There were some good views. There were a couple of people up there taking photographs. And all of a sudden, I noticed all of our hair started sticking up into the air,” he recalled.

“We thought it was something funny.”

McQuilken says he recalls that deadly afternoon in the Sierra Nevada mountains vividly: The flash of white light as bright as arc welding, the deafening explosion, the feeling of becoming weightless and being lifted off the ground. Most of all, McQuilken says, he remembers the sheer power of a bolt from above.

“I never was cautious before that,” says McQuilken. “Now, if I’m out to climb a peak, I’m the first person to bail if clouds gather.”

Contrary to rumors and some published reports, both brothers survived the strike, although another hiker was killed. There were 19 deaths reported in August 1975, in a year that saw a final toll of 91. Back then, however, lightning deaths weren’t well reported or tracked, he says, and the Moro Rock death wasn’t included.

Still, the photo serves as a gripping reminder and to help keep people safe from lightning, which has killed an average of 53 people a year over the past 30 years.

Now, McQuilken says people email him about once a week asking about that hair-raising photo, which has seemed to develop of life of its own.

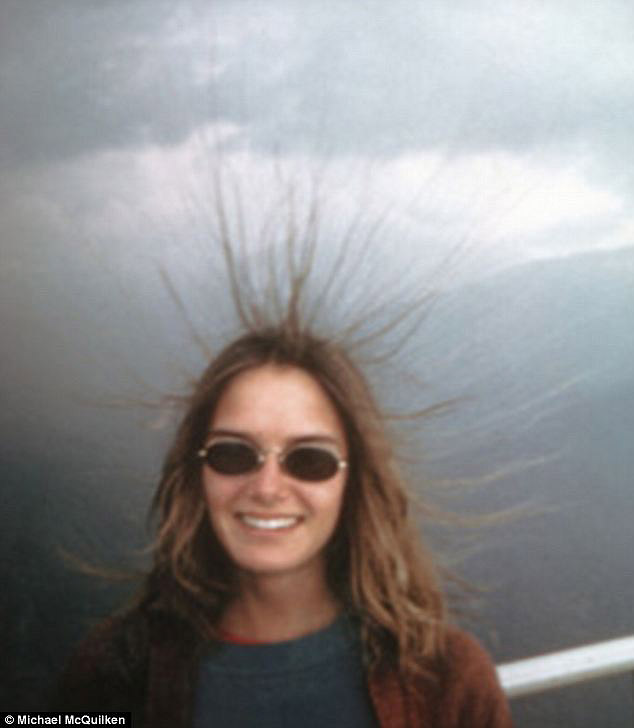

Famous photo was taken by his 15-year-old sister, Mary, using an old Kodak Instamatic camera, McQuilken said. He and his siblings were hiking the granite dome. When they reached the top to enjoy the view, someone noticed that their hair was standing on end.

“At the time, we thought this was humorous,” McQuilken recalled. “I took a photo of Mary and Mary took a photo of Sean and me. I raised my right hand into the air and the ring I had on began to buzz so loudly that everyone could hear it.”

Not once did they consider that a lightning strike was imminent, he said. Suddenly, the temperature dropped dramatically and it began to hail. The teens decided to return back down the mountain, but partway down, the bolt struck.

“I found myself on the ground with the others,” McQuilken recalled. “Sean was collapsed and huddled on his knees. Smoke was pouring from his back.”

It turned out that Sean was one of at least three people hit directly that day by the triple-pronged bolt, including one man who died and another who sued the U.S. government for not warning about lightning danger. The lawsuit was dismissed.

Sean was knocked unconscious and suffered third-degree burns to his back and elbows.

Although the kids didn’t know it then, hair standing on end and tingling skin may be signs that a lightning strike may be imminent, experts say. If that happens, the best advice is to seek shelter immediately. If that’s not possible, squat low to the ground on the balls of your feet, making yourself the smallest target possible and minimize contact with the ground. Then, as soon as possible, get out of the area.

After the strike, McQuilken and his family stayed in contact with local rangers and sent them slides of the now-famous photos. Years later, his sister surprised him with a calendar that included a pirated copy of the picture.

“That whole experience just feels like it happened yesterday,” says McQuilken, who lost his brother Sean to suicide in 1989.

He still spends a lot of time outdoors, but McQuilken takes no chances with lightning. He has been known to caution other hikers when it’s too dangerous to climb, but it’s clear that, like those boys on the mountain, they, too, think their chance of injury is remote.

I’ve told them, ‘This is not safe,'” McQuilken says. “But they seem to take what I say very lightly.”

I was there that day. I remember it very well. I have many photos of the same day. My family hair on end. My father was the man that was unconscious for 6 months. His hair did grow back. He was kept in a comatose state due to severe burns.

He unfortunately committed suicide as well in 2007. My parents did sue the federal government for failure to warn of the dangers. It was dismissed by threats of countersuit.

My father lived through the lighting incident. Unfortunately he never completely healed from it. I believe it is what caused his suicide after many years of anguish.