HOW TO START A ROCK GARDEN

Rock Gardens

It is probably best to avoid the word rockery, for this is apt to encompass all that is unsatisfactory about most small garden efforts in this field. A pile of soil is made — no doubt left over from something else — then scattered at random with bits of stone or even (horror upon horrors) broken concrete. The result is not a rock garden and it must be hoped that aubrieta and alyssum spread quickly to hide the hideous heap.

It should be said that a successful rock garden is one of the most difficult garden features to position, to construct and subsequently to maintain. What, then, are the attractions ? There are, of course, many. There is the wish to bring into the garden a piece of real, wild, ‘natural’ countryside; the sort of countryside which is almost of necessity, the most distant and different from the position offered by most small gardens. The natural rock, it is fondly hoped, stretches down deep into the earth to be a part of the truly natural world. Often in the wild such rocky outcrops are crossed by tinkling streamlets, deep pools reflect the clear sky and overhanging ferns. Such places are redolent of holidays and freedom, not the workaday world.

For these very reasons it is inevitable that to recreate such an idyll on a garden scale is virtually impossible. Also, much of the peace and calm of the natural scene comes through the near monochrome effect. A few harebells, a cushion of thyme, a patch of moss — each changing with the seasons — is the only bright color. The moment we add our rock garden plants, gathered for their spectacular beauty, from mountainous areas all over the world (and often made even brighter by hybridisers) we detract from the ‘natural scene’. Yet the other prime reason for building a rock garden is to grow these very plants. The paradox seems hard to avoid, but it is not impossible.

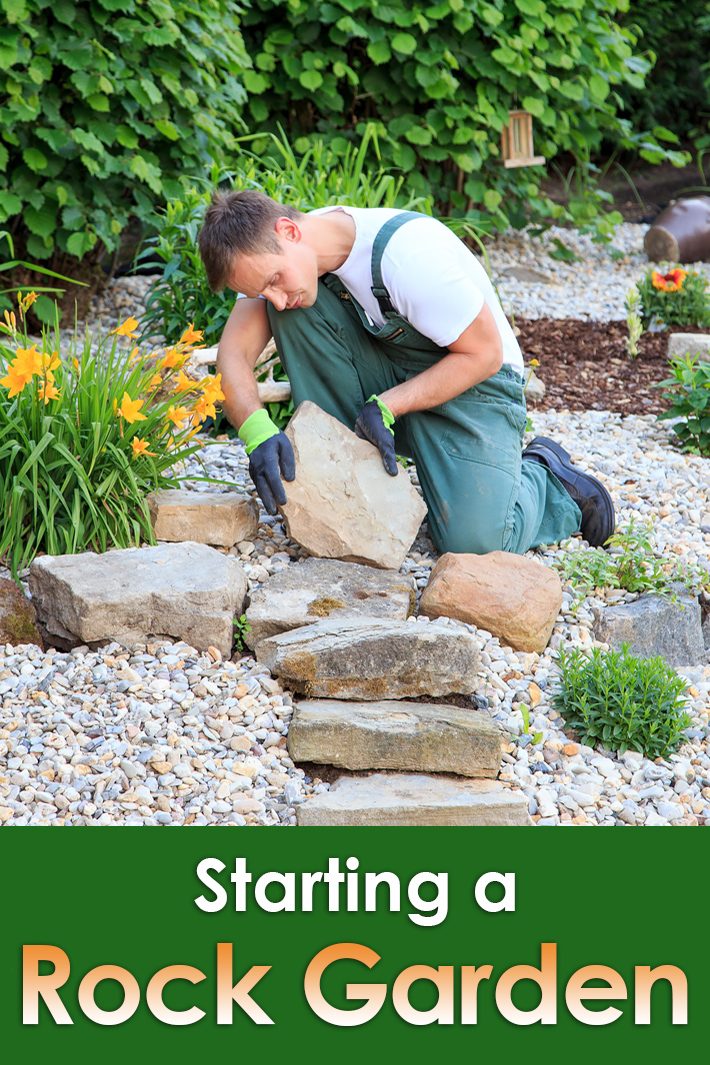

Creating a Rock Garden

A first essential is to know what is wanted — is it the effect of natural rock, or is it the plants that are most important? If it is the former, then the careful siting of, perhaps, only four or five fine, big rocks in an important focal point is what should be attempted. This is really creating sculpture with natural materials, and is only possible in an area where stone is freely available without great expenditure. But it is better kept this way, for rock work in areas where natural stone does not exist cannot fail to appear artificial. It is this obvious cosmetic artificiality that must be avoided if successful garden design is to be achieved.

The Rocks

When used for an architectural or sculptural role rocks must be chosen with great care. Cherish sides which show the effects of natural weathering; try to preserve any moss and lichen that already exist. Plan to hide scars or newly-broken faces which may take a long time to mellow.

Early treatises on rock gardens usually recommended that to give the feeling of natural rocky outcrops, stones should be laid, as if they were icebergs — with much more out of sight than visible. We can no longer afford such extravagance, nor is it necessary. However the basic tenet still holds good: no rock should just sit on the soil surface, its base should be hidden so that it appears to go deep down to parent rock.

The other vital fact to keep in mind is the way the natural lines in the rock go. This is its stratification and indicates how it was originally laid down millions of years ago. Such lines must be carefully followed and the angle chosen must be repeated for the whole outcrop — near to horizontal with a backward tilt is best (rock stratification lines are virtually never vertical). This is to suggest that the few rocks seen are the top of a rocky outcrop from which soil has been eroded.

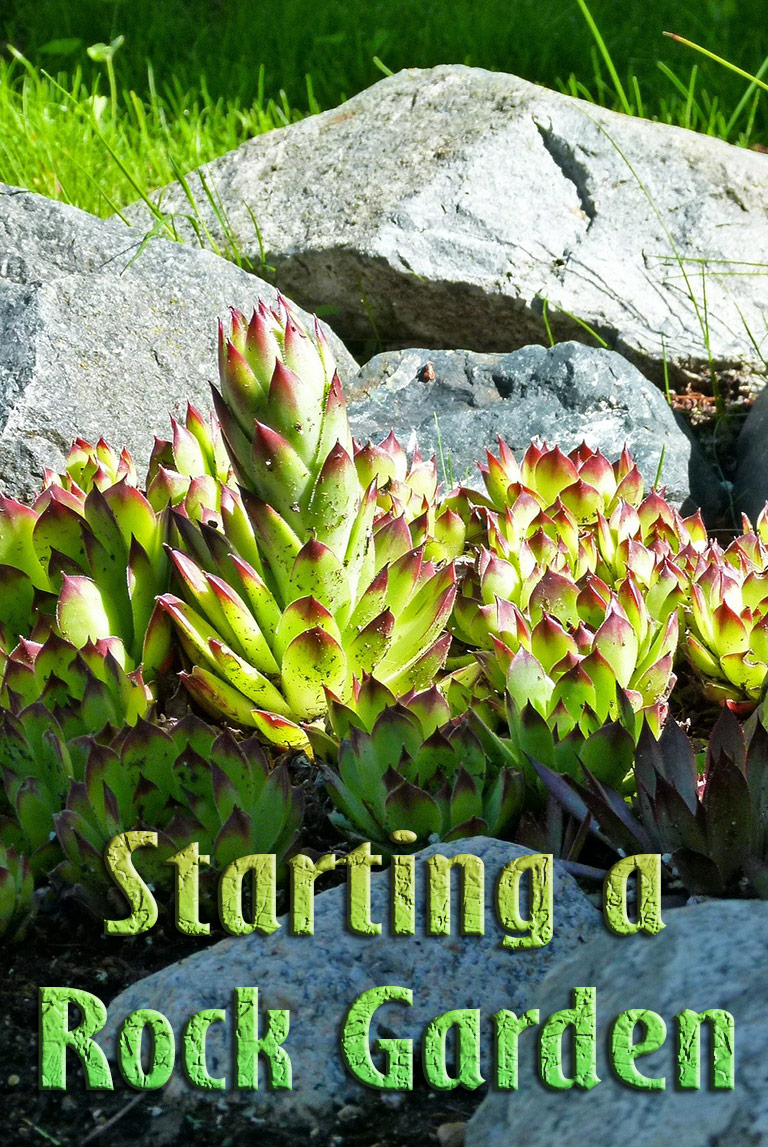

This type of rock garden needs few plants. Grass or water should come right up to the foot of the rocks and a strongly shaped conifer such as Juniperus sabina tamariscifolia or perhaps one of the spurges like Euphorbia wulfenii will add to the architectural effect and help to blend it into the rest of the garden scene.

Planting the Rock Garden – Read Here

Please follow us on Pinterest and enjoy our collection of recipes, crafts, fitness, health tips, gardening, DIY and more…

Leave a Reply